Instructions as Code for AI Analytics

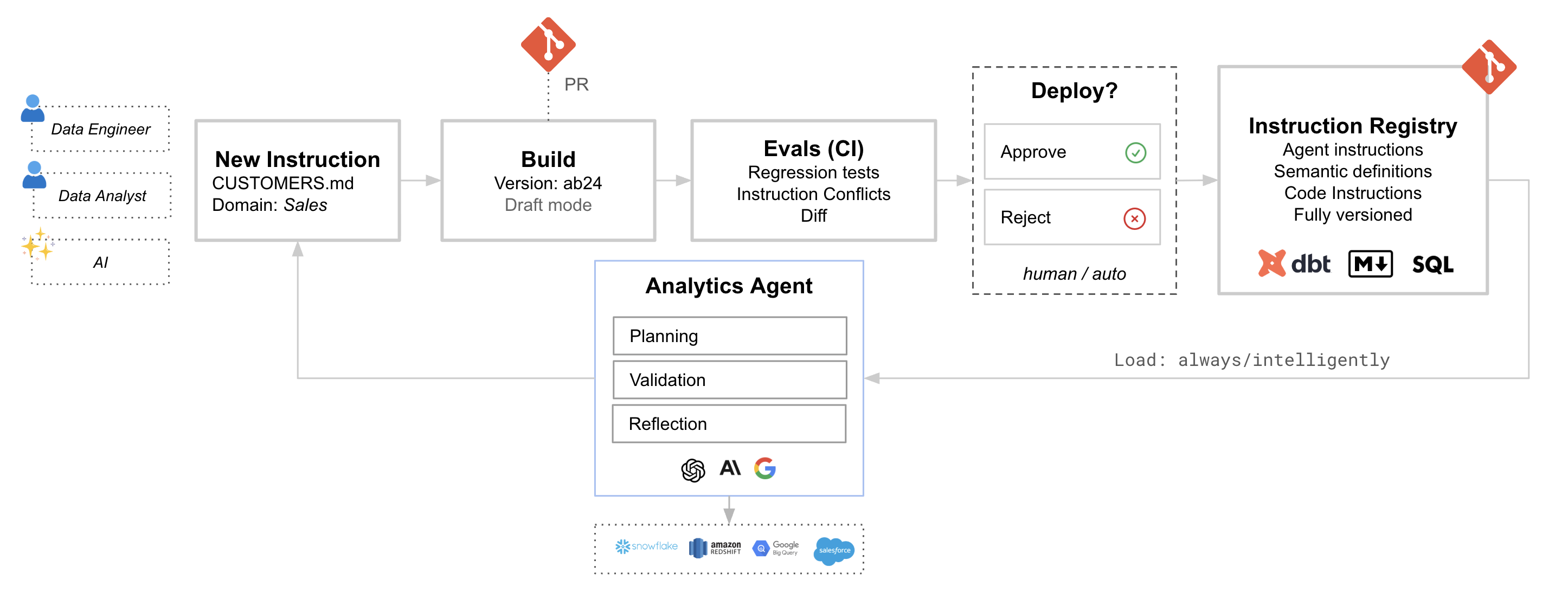

How to manage AI analytics instructions and semantic definitions with Git, pull requests, and automated tests. The result is consistent, reviewable AI behavior as definitions and schemas evolve.

Your AI analyst knows what “active customer” means because someone wrote it down. That definition lives somewhere: a markdown file, a dbt model’s description, or someone’s head. When that definition changes, what happens? Does the analyst pick it up automatically? Do your tests catch the shift? Does anyone review the change before it goes live?

This is the problem of managing context for AI systems. If you’ve used Cursor rules to guide how your coding assistant behaves, instructions work the same way for your AI analyst. They’re rules that define how the AI should interpret your data, what formulas to apply, and which domain conventions to follow. The knowledge that grounds your analyst (business definitions, calculation formulas, domain rules, SQL patterns) shouldn’t live in a UI or be scattered across team members’ heads. Treating these rules as code brings the same rigor you already use for data pipelines: version control, code review, automated testing, and a single source of truth.

The case for instructions as code

If you already manage dbt models in Git, you understand the value of version control for data logic. The same reasoning applies to the context that guides your AI analyst:

Version control gives you a full history of what changed, when, and why. When the analyst starts behaving differently, you can trace back to the exact commit that shifted its understanding.

Code review means team members review instruction changes before they go live. A data engineer can catch that a metric definition conflicts with an existing dbt model. An analyst can flag that a business rule misses an edge case.

Automated testing runs evals on every pull request. If a change to “revenue” breaks three test cases, you find out before it reaches production, not when a stakeholder asks why the numbers look wrong.

Single source of truth keeps documentation in sync with your data models. Your dbt models and your AI instructions evolve together, referencing each other naturally.

The goal is to make the AI’s knowledge as reviewable and testable as your transformation layer.

Anatomy of an instruction

Instructions are rules that shape your AI’s behavior, the same way Cursor rules tell a coding assistant how to write code. They can be anything from a one-line metric definition to a detailed domain guide. In practice, most teams use markdown files with frontmatter that controls when and how each rule applies.

Here’s a simple example:

---

alwaysApply: true

references:

- customers

- orders

---

# Customer Lifetime Value

CLV = SUM(order_total) WHERE customer_id = X AND status = 'completed'

Use 12-month lookback window from analysis date.The frontmatter tells the system this definition should always be loaded when relevant tables are in scope. The content itself is plain language, exactly what you’d write in a data dictionary or explain to a new analyst.

Instructions can also come from your existing documentation. dbt model descriptions, LookML views, even well-structured markdown files in your repo can become instructions automatically. The AI reads the same documentation your team reads.

The workflow: from change to production

The power of treating instructions as code comes from the workflow it enables. Changes follow the same path as any other code change: branch, review, test, merge.

1. Create or modify an instruction

A data engineer updates a metric definition. An analyst adds a new domain guide. An AI suggests an instruction based on observed patterns. All of these start as changes in a Git branch.

2. Build a draft version

When you push to a branch, the system syncs and creates a draft build. This is a complete snapshot of your instructions at that point in time, isolated from production and ready for testing.

3. Run evals in CI

Your test suite runs against the draft build. Each test case asks a question and checks that the agent’s response meets expectations: Did it use the right tables? Did it apply the correct formula? Did it follow the expected workflow?

The evals catch regressions before they reach production. If your change to “active users” breaks three existing test cases, you find out in the PR, not after merge.

4. Review and approve

The PR shows what changed and how it affected eval results. Reviewers can see the instruction diff alongside the test outcomes. This is where domain experts catch edge cases and data engineers verify consistency with the warehouse.

5. Merge to main

When the PR merges, the draft build becomes the live version. Your AI analyst immediately picks up the new definitions. The change is recorded, reviewable, and reversible.

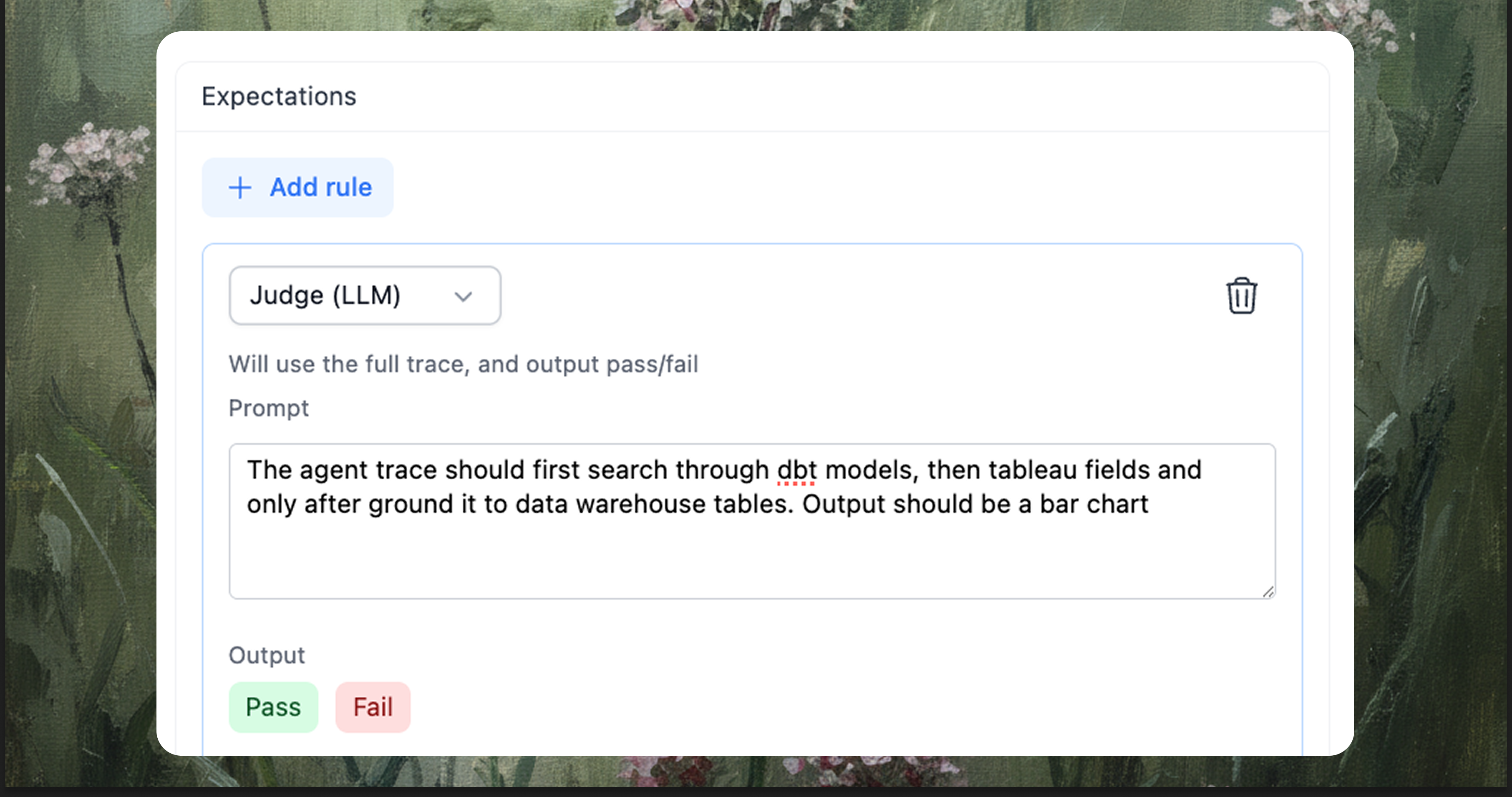

Evals as the safety net

The workflow only works if you have tests that actually catch problems. Evals are the automated checks that run on every change, combining deterministic rules (did the query use the right tables?) with judgment-based checks (did the agent follow the expected workflow?).

When a PR opens, the test suite runs. When it passes, reviewers have confidence the change is safe. When it fails, you have a clear signal that something needs attention. For a deeper dive into building an eval suite, see Evals and Testing for Agentic Analytics Systems.

What triggers a run

Not every change needs a full eval run. But some changes definitely do:

- Instruction changes: A metric definition update, a new domain guide, a modified SQL pattern

- Schema changes: A new table, a renamed column, a changed data type

- dbt changes: Model refactors, metric updates, source modifications

- System changes: LLM provider switch, temperature adjustment, tool configuration

The goal is to catch drift before it becomes a production issue. When your “active users” definition changes from “spent $5 in 14 days” to “spent $10 in 30 days,” the eval suite should fail if existing tests expect the old behavior. That failure is the prompt to update either the tests or reconsider the change.

Practical setup

The workflow integrates with standard CI/CD tools. A typical GitHub Actions setup:

- On PR open: Sync the branch, create a draft build, run evals, post results to the PR

- On merge: Publish the draft build to production

The sync creates an isolated environment for testing. The evals run against that environment. The results inform the review. The merge promotes tested changes.

name: Instructions CI/CD

on:

pull_request:

paths:

- '**/*.md'

- 'models/**'

push:

branches: [main]

jobs:

test:

if: github.event_name == 'pull_request'

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Sync branch

run: # Create draft build from branch

- name: Run evals

run: # Execute test suite against draft

- name: Post results

run: # Comment on PR with pass/fail summary

publish:

if: github.ref == 'refs/heads/main'

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: Publish build

run: # Promote draft to productionThe specifics vary by platform, but the pattern is consistent: sync, test, report, promote.

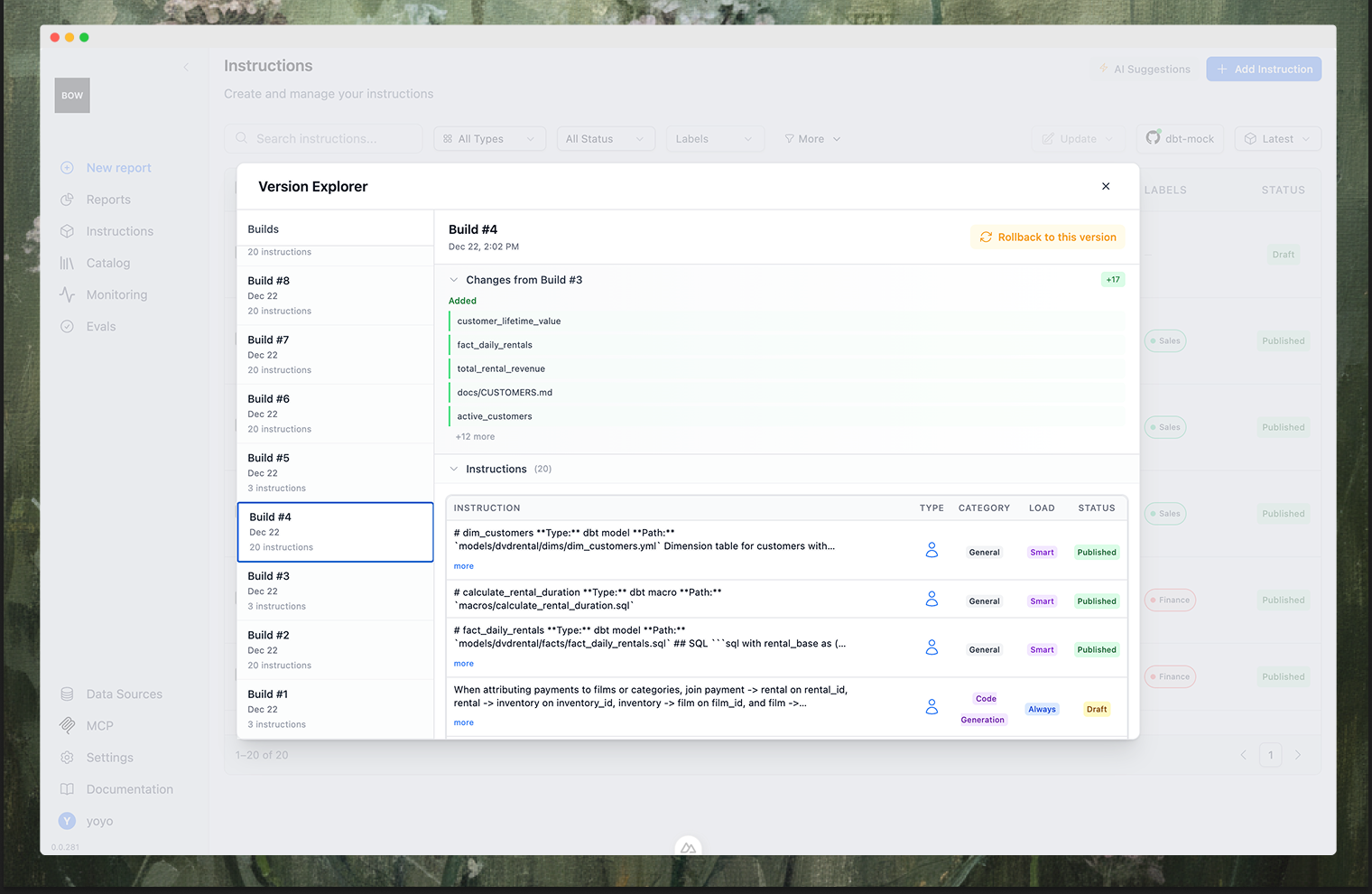

Versioning and rollback

Every sync creates a build: a versioned snapshot of your instructions. You can browse the history, see what changed between builds, and roll back to any previous version if something goes wrong.

This is the safety net that makes the workflow practical. If a change causes unexpected behavior, you don’t have to debug what went wrong immediately. You can roll back to a known good state, restore production behavior, and investigate at your own pace.

When things go wrong

Sometimes a change needs to bypass the normal flow. An urgent fix, a hotfix for a production issue, a quick correction that can’t wait for CI.

The escape hatch is to edit directly and unlink from Git. The instruction becomes user-owned, no longer synced from the repository. This is intentional friction: it’s visible that something was changed outside the normal process, and the change should eventually be reconciled back to Git.

The goal isn’t to prevent all manual changes. It’s to make the normal path (version controlled, tested, reviewed) the path of least resistance.

Closing thoughts

Treating instructions as code isn’t about adding ceremony to simple changes. It’s about bringing the same reliability practices that work for data pipelines to the context that guides your AI analyst.

When definitions live in Git, you get history. When changes go through PRs, you get review. When evals run automatically, you catch regressions before production. When builds are versioned, you can roll back if something goes wrong.

The AI analyst is only as reliable as the context it works from. Version control, automated testing, and code review make that context as trustworthy as your dbt models, and as easy to maintain.

Start simple: put your most important definitions in markdown files, connect them to your repo, write a few test cases for common questions. The workflow will grow naturally as you encounter edge cases and catch issues that would have slipped through before.

The goal is an AI analyst that behaves consistently even as the context around it evolves, and a team that can maintain that context with confidence.